Baseball’s commissioner is dead wrong about Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson.

The pun is intentional. Rob Manfred said he lifted baseball’s ban of Rose this week because Rose died in September. Manfred lifted bans on 16 other deceased players, too, including Jackson.

“Roll over Pete Rose, and tell Shoeless Joe Jackson the news,” began a story on the announcement by one of my favorite baseball writers.

“Obviously, a person no longer with us cannot represent a threat to the integrity of the game,” Rob Manfred wrote as part of the announcement that he had lifted baseball’s lifetime ban of Rose for gambling on baseball.

That reasoning is wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. It’s intellectually bankrupt.

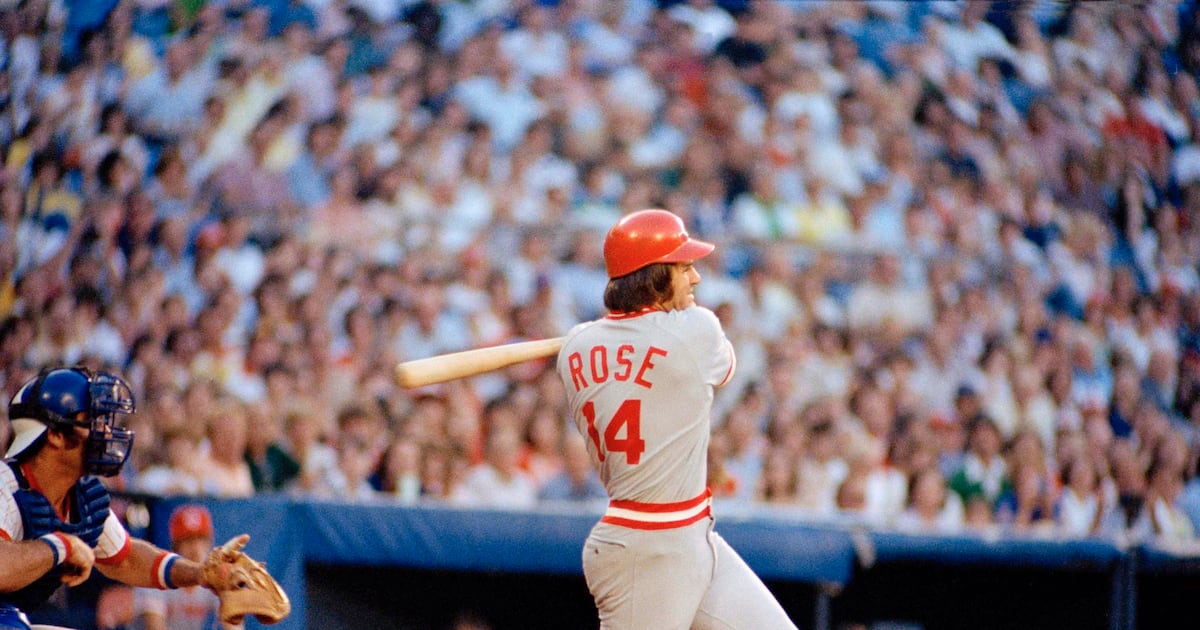

Rose earned the ban for betting on baseball while he was playing the game. Worse, he bet on his team while he was its player-manager. There is nothing more threatening to the integrity of a game than the potential for cheating by players and managers to help their team win or lose or giving gamblers access to inside information.

An existential threat to baseball

Dead or alive, Rose’s actions and legacy represent an existential threat to whether fans can trust what happens on the baseball field. Period.

Think of it this way. Do you remember how you felt when you lost a game when you were 8 to 12 years old? Or your favorite team lost a crucial game when you were those ages? Do you have a child or grandchild who now lives or dies with their favorite Premier League or NBA team’s wins and losses?

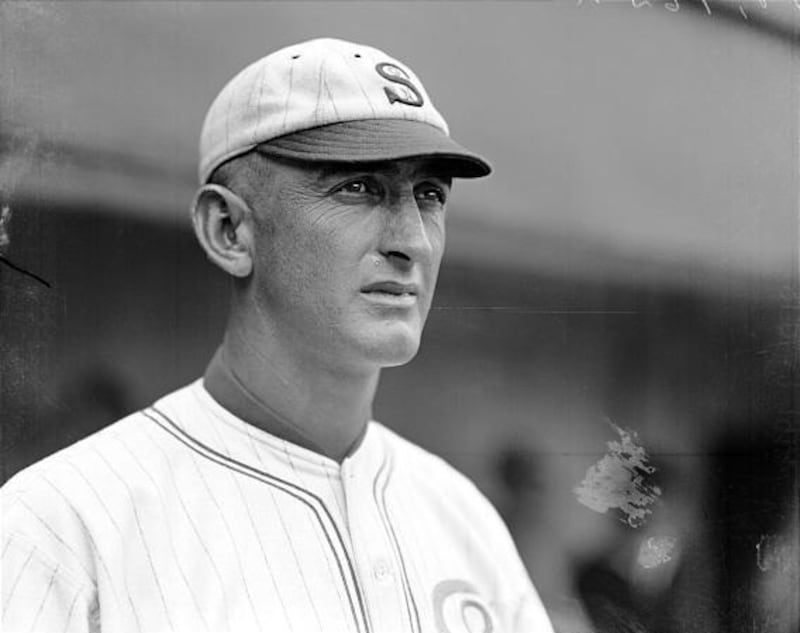

Now imagine learning your favorite player or the team manager lost that game on purpose. It’s no surprise the most plaintive cry in the history of sports is said to have been uttered by a young Chicago White Sox fan who learned his heroes, allegedly including Shoeless Joe, took money from gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series:

“Say it ain’t so, Joe.”

Manfred isn’t bending the rules here. He literally reinterpreted them. Rose, Jackson and the others were never given lifetime bans. They were banished to a list of people permanently ineligible to be part of the game. Manfred’s announcement changes one of baseball’s chief rules, which is posted on every clubhouse door:

“Any player, umpire, or club or league official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible.”

Manfred is altering what he called the “interpretation” of the meaning of “permanently ineligible.” Permanence now ends with death.

That sounds metaphysical.

Did Rose atone for his gambling sins?

Interestingly, many of Rose’s peers think of the dilemma — should he be voted into the Hall of Fame in December 2027, when he’ll first be eligible, or not — in terms often reserved for faith.

“There wasn’t remorse there,” friend, former teammate and born-again Christian Mike Schmidt told The Athletic. “He didn’t show any atonement for his admission to betting on baseball.”

“Baseball loves you, they want to forgive you,” former teammate Jim Kaat told Rose in the midst of a decadeslong run where Rose steadfastly lied that he never bet on the game.

Another teammate, Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, said he would never visit the Hall again if Rose were inducted.

But Tony Perez and others said Rose paid the price for his sins and should be inducted.

Baseball applied justice to Rose. Is he now due mercy? Living Hall of Famers are split 50-50, Schmidt said.

I feel split 50-50, too. Rose was not one of my favorite players as a boy. He played for the Reds, not the Red Sox. Yet he was one of my favorite players to watch. His nickname was Charlie Hustle, and he taught me to hustle when I played baseball. His example taught me to respect the game.

How could someone who respected the game so intensely treat it with so much disrespect by committing its cardinal sin and then lying about it hundreds, if not thousands, of times?

Most of the arguments I see for enshrining Rose in the Hall of Fame center on the fact that the Hall is a museum. That word is part of its name. And baseball’s museum should include Rose because he is the game’s all-time hits leader and one of its best players.

It’s a good argument, but it breaks down on inspection. First, induction in the Hall of Fame is considered baseball’s “highest honor,” according to a past president of the Hall. Second, the Hall’s chairman has pointed out that the museum displays 31 examples of Rose’s memorabilia and records throughout the building, according to Kaat.

Induction vs. inclusion in the Hall of Fame

So if someone argues that baseball’s Hall of Fame and Museum must include Rose to tell the game’s full story, well, it already does.

So the question distills to this: Does Rose deserve induction, enshrinement and a plaque in the hall of greats, or is it enough to include his history all over the museum?

During Rose’s life, the latter was good enough for Manfred, who in 2015 denied Rose’s latest plea by saying Rose had “not presented credible evidence of a reconfigured life either by an honest acceptance by him of his wrongdoing … or by a rigorous, self-aware and sustained program of avoidance by him of all the circumstances that led to his permanent ineligibility in 1989.”

Let’s set aside Manfred’s flip-flopping and consider Shoeless Joe’s own appeal to God. The actor D.B. Sweeney‘s depiction of Jackson in the movie “Eight Men Out,” and the way he was portrayed in the book of the same name, made Shoeless Joe one of the most sympathetic figures in sports history.

“The Supreme Being is the only one to whom I’ve got to answer,” Jackson once said.

“I’m not what you call a good Christian,” he said another time, “but I believe in the Good Book, particularly where it says ‘what you sow, so shall you reap.’ I have asked the Lord for guidance before, and I am sure he gave it to me. I’m willing to let the Lord be my judge.”

A Watergate perspective

Eight years ago, I got to sit down in Oxford, England, with a man who had a ringside seat to the Watergate trial. He was the clerk to the judge, and they sat together in stunned silence in the judge’s chambers when they became the first people to hear the taped evidence of President Richard Nixon saying he would pay $1 million to pay off the Watergate burglars to cover up the crime.

“A weak conscience, and certainly a numbed conscience, opens the door for ‘Watergates,’ be they large or small, collective or personal — disasters that can hurt and destroy both the guilty and the innocent,” said that former clerk, Elder D. Todd Christofferson, now a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Rose’s lack of contrition sticks in the craw of extending posthumous mercy.

Schmidt said Rose didn’t show atonement even when he admitted to betting on baseball. Atonement means to make one again two parties separated by disagreement or sin — in this case, baseball and Rose. The purpose of atonement is to correct or overcome the consequences of sin or error.

For Christians, God’s mercy can atone for the sins of a person who repents or turns their heart from their sins.

Rose remained unrepentant even after he admitted he bet on the game, and his sins remain a threat to baseball, even as it and other sports make partnerships with gambling companies.

The beauty of applying faith in this or any context is that in Christianity, God is loving and kind and provided a Savior whose grace can overcome all our faults, weaknesses and sins. He is said to grant beauty for ashes.

That and one final common argument made for Rose is how I get to 50-50 on whether he and Jackson should be inducted.

Making the final call

That logic says that the Hall of Fame is already a rogue’s gallery full of racists, gamblers and cheaters who used performance-enhancing drugs. Rose would be one of the latter, too, since he is well known for taking the greenies (amphetamines) freely available in baseball’s clubhouses in the 1970s.

That sounds too much like many wrongs should make a right, but maybe there is something to this argument. It’s a hall of humans, after all, each flawed like the rest of us. They may be referred to as gods of their game, but maybe the lesson is that it is a mistake to immortalize them too much, that our baseball idols need grace and God the same as you and I.

I’m not ready to make a call on whether inducting Rose or Shoeless Joe would turn the ashes of their actions into beauty. We live in a world of hot takes. Pete Rose certainly was full of them. His situation generates them like a gatling gun.

It seems to me that hot takes rarely offer much grace or mercy, though.

It’s a good thing then that we, like the committee of former players who will vote on Rose’s Hall of Fame induction, will have 30 months to think deeply about right and wrong.