Baseball bat manufacturers had little evidence to suggest a spike in sales was just around the corner when Major League Baseball’s newest season opened last week.

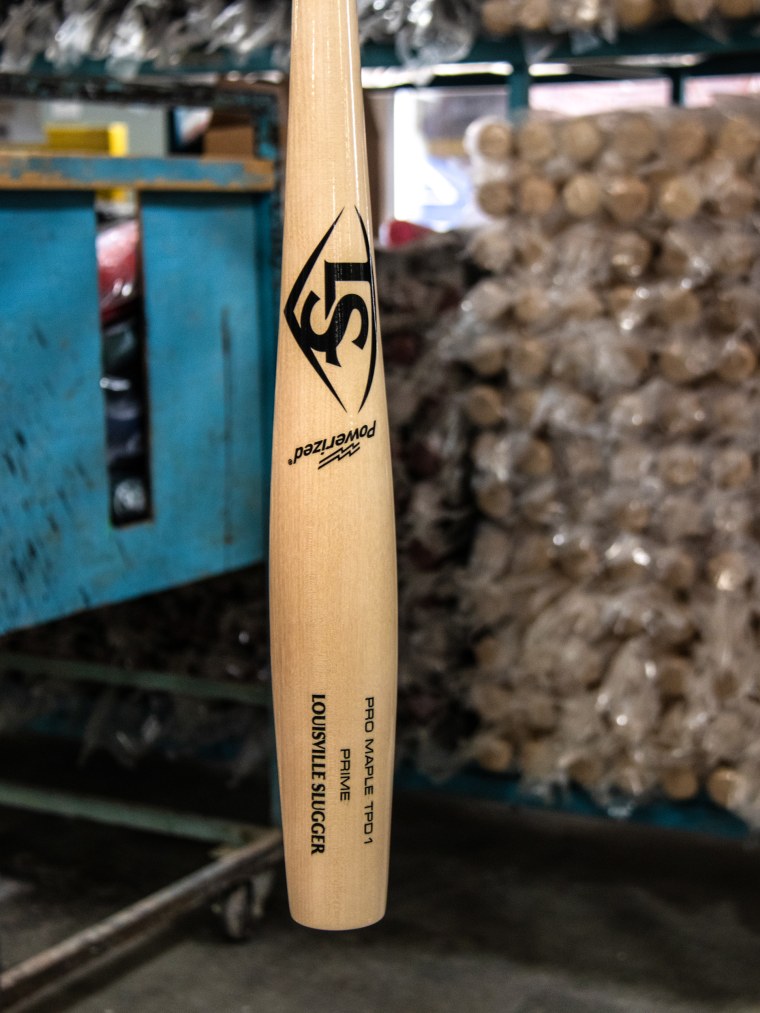

It had been four years since physicists working for MLB teams had begun chatting with Louisville Slugger about how to increase the exit velocity of batted balls. Those conversations helped create a shape — resembling a bowling pin, with a thicker middle and a tapered barrel — that the company first turned into a real, wood bat in November 2023. Four teams contacted Louisville Slugger about the model, but when the so-called torpedo bat was introduced around big-league clubhouses last season, adoption was hardly widespread.

On the eve of the new season, less than 10% of MLB hitters using bats made by Marucci Sports were using the so-called torpedo model, said Kurt Ainsworth, the company’s chief executive. “When you’re a baseball player, you’re used to some looking down the bat and it looks one way,” Ainsworth said. “And then you see it, it looks kind of funny. Like, ‘I don’t really need that.’”

That stance changed last weekend when the bats erupted into the public’s attention — and with them, overnight big business. Ainsworth estimated that half of Marucci-affiliated hitters have now tried a torpedo model and said he expects that to increase to 80% by month’s end.

“All I can say,” said Bobby Hillerich, a vice president of manufacturing and operations for Hillerich and Bradsby Co., the maker of Louisville Slugger bats, “is that it’s crazy.”

“There are 1,500 preorders for a bat that doesn’t exist, and there’s no website yet,” he said.

“Torpedo bats” officially entered the sports lexicon after the Yankees hit an MLB-record 15 home runs in three games, including a combined nine by five Yankees hitters using the new bats, which shift the “sweet spot” closer to where hitters typically make contact. Sometimes, the shift can be as much as 6 inches. The bats’ existence might have gone unnoticed, however, if not for Yankees broadcaster Michael Kay.

On social media, a clip of Kay describing the bats’ origin story — a Yankees study had found certain players weren’t hitting the ball with the barrel of the bat, but lower toward its handle, prompting an MLB-approved design change moving more mass toward the handle — went viral.

“This has been all over the country and really around the world, people talking about bats and this bat design, and it just shows you the impact of what the Yankees can do when something happens there,” Ainsworth said.

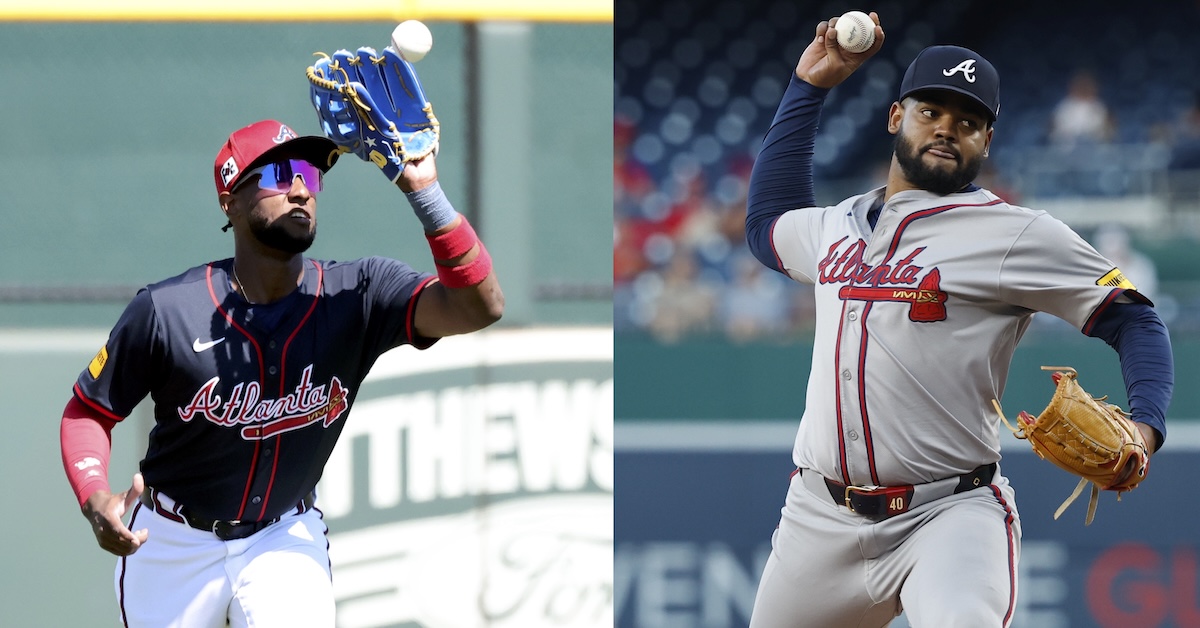

Ever since, phones have been ringing in the offices of the 41 MLB-approved batmakers. One such call came Monday morning from the Cincinnati Reds, who asked a Louisville Slugger executive and sales rep to drive samples to their ballpark 90 minutes away as soon as possible. Within hours, Reds star Elly De La Cruz was testing a sample torpedo bat in batting practice and liked it so much that he kept it for that night’s game, in which he went 4-for-5 with two home runs.

On Monday, Louisville Slugger had developed 20 different models with varying tapers, lengths and weights. By week’s end, Hillerich estimates, that number will rise to closer to 70 to respond to MLB teams’ requests for adjustments and to meet trickle-down demand it anticipates from youth and collegiate wood-bat leagues. One of the biggest wrinkles Hillerich has encountered is ensuring Louisville Slugger has enough wood — its company largely uses birch for MLB hitters — to meet demand.

“We have two log buyers that go out, and they usually go out once every two weeks,” he said. “I told them to get on the road Monday morning and not come back.”

For Marucci, which uses largely maple in its professional bats, sourcing wood isn’t an issue, as it owns a timber company in Pennsylvania and two mills. (In addition, metal bats used in youth and collegiate leagues are Marucci’s biggest seller, he said.) The logistical challenge has been turning around bats quickly enough for its roster of MLB players.

At Marucci’s headquarters in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a bat tailored to an MLB hitter’s specific swing and balance points can be produced and in the hitter’s hands in about a week. Although Ainsworth said a true torpedo model might not make much sense for younger players, who rarely make contact in the same place and need larger barrels, the company clearly anticipates strong demand from the public, as well as the pros. By midweek, a banner had been placed across the top of the Marucci website leading to the company’s three different torpedo models: “The bat everyone’s talking about is here.” Victus, a Pennsylvania-based batmaker Marucci acquired in 2017, had a similar landing page on its website.

“I will tell you that it has been a nice bump for the company,” Ainsworth said.

Yet for Ainsworth, the biggest winner from the surge in interest produced by the bats was baseball itself. For years, the sport has battled an existential debate about whether it had enough stars with crossover cultural appeal and whether its slower pace of play and stodgy tradition could attract younger fans. For the past week, however, as the NBA playoffs and the NFL draft approach, the buzz has been about baseball.

Louisville Slugger, which Wilson Sporting Goods has owned since 2015, has experienced sales spikes before. Rick Redman, a vice president of corporate communications at Hillerich and Bradsby who has worked in public relations for Louisville Slugger for 22 years, said the last time he could recall a product this hot was 2006, when Louisville Slugger produced pink bats for Mother’s Day.

And sales of souvenir bats quadrupled in 2016 when the Chicago Cubs broke a 107-year-old World Series drought, Hillerich said. Yet the demand curve for torpedo bats could look similar to the skyrocketing arc of one of the Yankees’ weekend home runs, because, unlike a novelty item, they represent an innovation that could shake up a century-old game.

Pitchers have used data and technology in recent seasons to throw harder. Hitters, meanwhile, were still playing catch-up by changing how, not what, they swung. For batmakers, that gap between hitters and pitchers created a market opportunity. Both Louisville Slugger and Marucci operate high-tech hitting labs to test their equipment. In recent years, Ainsworth, who played four MLB seasons as a pitcher before he co-founded Marucci in 2004, had become inspired by applying golf’s use of different clubs for different purposes to baseball.

“You go into an industry that’s been, I don’t want to say stale for a while, but it’s been in America’s pastime, the player uses the same bat versus every pitcher,” he said. “You don’t use the same golf club for every shot. Why in baseball were we using the same bat?”

In 2022, Paul Goldschmidt became the National League’s most valuable player using a Marucci bat with a knob shaped like a hockey puck, which shifted the weight below the hitter’s hands. The design differed from that of the torpedo bats, but the idea was the same: What is the optimal design to create the biggest opportunity for hits? Some have pushed back against the effectiveness of the new design, such as Milwaukee manager Pat Murphy, whose team allowed the 15 home runs to the Yankees.

“My old ass will tell you this, for sure: It ain’t the wand, it’s the magician,” Murphy told reporters last weekend.

Not everyone agrees with the theory. Aaron Leanhardt, a former physicist who now works for the Miami Marlins, has been credited with working with various batmakers to develop the bowling-pin design during his time with the Yankees after he discovered that some Yankees hitters rarely made contact on the barrel.

Both Marucci and Louisville Slugger officials said that the bowling-pin model first became a reality late in 2023 and that a few players used it last season, including New York Mets star Francisco Lindor and Yankees slugger Giancarlo Stanton, who hit seven postseason home runs using such a model. Cody Bellinger, then with the Chicago Cubs, tried a Louisville Slugger model but wasn’t quite sold until he joined the Yankees this season and tested newer models tweaked to his preferences. He was among the torpedo users to hit home runs during New York’s explosive opening weekend. Yet the shape went unscrutinized last year. Why, then, did it take nearly a year and a half for the torpedo bat to capture the zeitgeist and affect the bottom line?

Hillerich agreed that the Yankees’ national exposure, combined with the intrigue of a new innovation, “just made for the perfect storm.”

“If Cody Bellinger would have struck out,” Hillerich said, “we wouldn’t be talking right now.”