There has been an acronym going around the NBA world lately that has been raising as many questions as alarms: DVT.

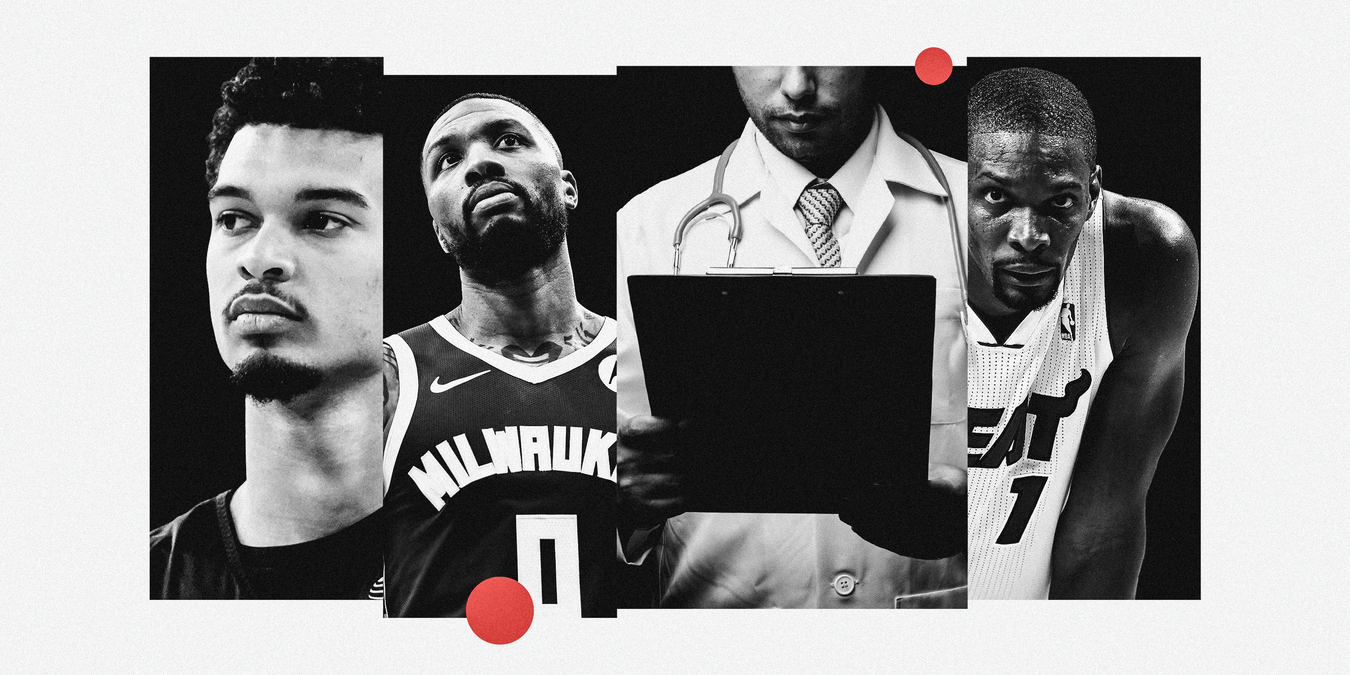

DVT stands for Deep Vein Thrombosis, a type of blood clot that often requires medical intervention. Two superstars, Damian Lillard and Victor Wenbanyama, have been diagnosed with a DVT over the last month.

Advertisement

Wenbanyama was ruled out for the remainder of the season by the San Antonio Spurs when a DVT was discovered in his right shoulder in February, while Lillard is still attempting to return for the Milwaukee Bucks in the playoffs after doctors found a DVT in his calf in March. Ausar Thompson, the Detroit Pistons’ high-flying 22-year-old wing, was diagnosed with a blood clot in March 2024 and did not return to the court until last November.

To understand how DVTs work and why they appear to be more frequent in the NBA, The Athletic spoke with multiple doctors to learn more about the ailment. Though they were not directly involved in treating these particular athletes, they have extensive experience with the various aspects of treating DVTs in other patients.

What is a DVT?

DVT is a type of blood clot typically occurring in the veins of the arms or legs, though they often have different causes and treatments based on their location. DVTs may initially present symptoms of soreness, swelling and heaviness in the affected area, which can be hard to recognize as something more than typical wear and tear for a professional athlete.

“(The symptoms are) not something that athletes would necessarily think is that unusual,” said Dr. Cheng-Han Chen, a cardiologist and medical director of the Structural Heart Program at Saddleback Medical Center in Laguna Hills, Calif. “It could just be that in the past, athletes were getting DVTs but shrugged it off.”

One of the primary risks of a DVT, particularly in the legs, is that the clot can become dislodged and travel to the lungs. This can cause a blockage in an artery known as a Pulmonary Embolism (PE), which can be life-threatening. The earlier doctors catch a DVT, the lower the risk of a PE occurring.

“The reason why DVTs are concerning — the lower extremity more so than the upper extremity — is their predilection to migrate to the heart,” said Dr. Vinay Badwhar, professor and chairman of the department of cardiovascular thoracic surgery at the West Virginia University Heart and Vascular Institute.

Advertisement

Though there have been three known diagnoses of DVTs in the NBA in just over a year, this is far from the first time blood clots have been an issue for NBA players. Miami Heat star Chris Bosh was ruled out for the remainder of the season in February 2015 when a clot was discovered in his lungs. Bosh then had to retire when another one was found a year later, with the NBA ruling the recurrence of a clot constituted a career-ending illness for the then 31-year old.

There have been more recent examples of players who had DVTs treated and resumed their careers, such as Raptors wing Brandon Ingram in 2019 and Lakers center Christian Koloko in 2023. Several other high-profile athletes, such as tennis icon Serena Williams and hockey great Zdeno Chara, have also received DVT diagnoses before undergoing treatment and eventually returning to action.

What causes a higher risk of DVTs?

Professional athletes can be exposed to heightened risk factors for DVTs for a number of reasons. Frequent plane travel can increase the risk of DVTs due to inactivity, though players are not flying drastically more of late than in the recent past. Studies have suggested taller people are at higher risk of a DVT. But as Dr. Chen noted, player heights have not changed significantly either.

Chen said repeated use of NSAID anti-inflammatory medications like Advil can increase the risk of DVT, which is notable since professional sports franchises are increasingly treating pain with NSAIDs instead of more dangerous opioids and painkillers.

But the primary concern is that players experience plenty of bruising from contact and push their bodies to the limit. Dehydration, as well as trauma to the extremities from repetitive motions and jumping, also accelerates the risk.

“It’s not genetics or familial. It just randomly happens in certain people and is more common in people that have repetitive arm movements,” said Dr. Christopher Yi, vascular surgeon at Memorial Orange Coast Medical Center in Fountain Valley, Calif.. “Wenbanyama, that’s probably what’s going on with him. In golf, Nelly Korda had that. It’s just sort of random people with repetitive arm movements.”

Advertisement

Jump shots certainly are among those types of arm motions. Yi notes how overuse of the arm and shoulder can cause the veins in the thoracic outlet to compress, known as Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS). TOS became more widely known in NBA circles when 2017 No.1 overall pick Markelle Fultz was diagnosed with it when his career sputtered early. This condition can slow down the normal flow of blood through the vein, increasing the risk of clotting.

Though most people associate the components of the shoulder with the ball and socket connection known as the Glenohumeral joint, TOS typically occurs in the Scalene muscles that run closer to the neck and chest. Important nerves, an artery and a vein run through the area under the clavicle bone and around the first rib, before going down under one of the pectoral muscles near the chest. Compression in these areas can cause TOS and lead to the development of DVTs.

How are DVTs treated?

Treatment for a DVT depends on location. For leg DVTs, such as Lillard’s, patients begin a blood thinner regimen as soon as possible and then monitor progress from there. Blood thinners are a group of anticoagulant medications that make it more difficult for blood to clot, mitigating the risk of DVTs but also making the body more prone to excessive bleeding from contact and cuts. Therefore, players typically are not allowed to play while on blood thinners.

“The recovery is unpredictable and it’s all based on how long it takes for the blood clot to dissolve,” Chen said. “Depending on the person, the time it takes for the blood clot to resolve could be anywhere from three months to a year. I understand why teams would be like, ‘We can’t give a timeline.’ Because if I were the doctor, I would tell the teams, ‘I can’t give you a timeline.’”

Because players cannot play on blood thinners, the goal is to clearly diagnose what causes the clotting. Li explained how the process typically would go for a player in Lillard’s situation.

“Trying to figure out what caused it and the length of treatment,” Li said. “Whether he needs to be on blood thinners for long-term or short-term. I’m not sure about his recovery and prognosis, but I’m not sure players in the NBA can continue competing at a high level being on blood thinners. Definitely not football, golf is probably OK but being on blood thinners in a contact sport can be pretty risky. Any injuries or heavy contact can cause internal bleeding.”

There are no clear indications for what will happen in the cases of Wenbanyama and Lillard. Both of their teams have expressed optimism for a full recovery, with Lillard attempting to return in time for the playoffs this month.

Bucks star Damian Lillard is still hoping to return for this season’s playoffs. (Dylan Buell / Getty Images)

For arm DVTs such as Wembanyama’s, there are surgical options to relieve the symptoms of TOS. Wenbanyama reportedly underwent surgery recently, and there is optimism that he will be ready to play for the French national team at the FIBA Eurobasket tournament at the end of August.

This is the procedure Ingram had in 2019 when he was diagnosed with a DVT early in his career. Doctors removed part of his first rib at the very top of his chest to relieve the pressure on the vein, then gave him blood thinners to allow the clot to dissolve. Removing the first rib is not of significant consequence because the area is well protected by the clavicle bone and surrounding ribs, according to Yi.

Advertisement

Once that happens, the patient then stops taking the blood thinners and has a recovery period until their blood coagulation returns to normal and they can be cleared for contact.

“It’s a procedure to remove the blood clot, a separate surgery to remove the first rib, and physical therapy after that,” Li said. “That process takes, maybe, up to a year to be back to your competitive form again and usually a full recovery.”

Li calls lower-extremity DVTs, such as Lillard’s, another beast because they are usually not caused by the compression from the bone like they are in the arm. These lower body DVTs appear to be more random, so blood thinners are the consensus treatment. The goal is to have them on blood thinners until the clot goes away, conduct ultrasounds and other imaging to examine for further clotting once off the medication, then let them ramp up their return-to-play protocol.

“If you get blood clots in the legs and they go to the lung, a PE, the recovery is much different,” Li said. “You need to be on long-term blood thinners. You may have longstanding effects on leg swelling and lung function. That’s when you sometimes see athletes have to retire.”

Regardless, players who are diagnosed with a DVT must continually be checked for further DVTs.

“Once someone has one, then you are a little more worried that it’s going to happen again,” Chen said. “Because something in their body is prone to cause that blood clot.”

Are there more NBA DVT cases?

Now that Lillard, Wenbanyama and Thompson have all been diagnosed with DVTs within about a year of each other, it begs the question of whether there is indeed a rise in blood clots among NBA players.

While experts who spoke to The Athletic acknowledge some of the changes to the game can put more strain on the body — players take more jump shots in the modern game and have to run more than ever — they do not think playstyle changes are the primary cause of an increase in DVT diagnoses. They all point to the increased awareness of DVTs from everyone to the athletes to the staff that helps them take care of their bodies.

Advertisement

“I wouldn’t necessarily say there’s a new epidemic of DVT,” Chen said. “It’s being diagnosed in a few high-profile players and it’s going to come even more to the forefront. When athletes start talking about leg soreness now, trainers are going to think, ‘Oh my gosh, do they have a DVT?’ Athletes and teams are much more attuned to the possible diagnosis of DVT.”

The silver lining for Lillard, Wembanyama and others who have suffered DVT recently: Their cases help ensure that more athletes catch potential DVTs before they become more serious.

“Chris Bosh was the first big one that we all noticed once he got it,” Chen said. “Now if an athlete has these symptoms, they say, ‘Maybe I should get this checked out and tell the trainer.’ And then the trainer is now more cognizant of it and more likely to do the testing for it.”

(Illustration: Demetrius Robinson / The Athletic; Photos: Thearon W. Henderson, Tim Nwachukwu, Mike Ehrmann / Getty Images)