Welcome to Sliders, a weekly in-season MLB column that focuses on both the timely and timeless elements of baseball.

When Jake Bird pitched in Triple A for the Colorado Rockies, his manager, Warren Schaeffer, noticed him playing chess on his phone. Schaeffer engaged him for a few games, and it wasn’t close.

Advertisement

“He’s a lot better than me, and he took it to me,” said Bird, now a setup man for Schaeffer in the majors. “He’s just really smart. He’s willing to see what guys like, willing to learn and communicate.”

Schaeffer, 40, has spent 19 years in professional baseball, all with the Rockies, half a lifetime in checkmate. He replaced Bud Black as manager on May 12, and the Rockies lost 17 of their next 19 games.

Winning baseball has always been elusive in Colorado, where — as Sports Illustrated’s Steve Rushin once wrote — the team wears the colors of a bruise. For the folks who take pride in working there, this is the biggest challenge yet.

“This is extremely personal to me,” Schaeffer, a former minor league infielder, said before a game in New York last weekend. “It’s all I think about, day and night. I’ve only ever been a Rockie, and the Rockies have never won the West. The Rockies have never won the World Series. These are all things that are very, very important to me, and I think the opportunity is ripe at the moment to start building for that.”

A few hours later, against the Mets, the Rockies led off by striking out on a pitch-clock violation. After a homer, the next 17 batters went down in order. The lopsided loss closed out May and clinched the team’s 22nd losing series in a row, a major league record.

The Rockies fell again the next day, becoming the first team ever to lose 50 games before winning 10. But that game was more competitive, the sixth out of seven losses decided by one or two runs. Losing is never acceptable, Schaeffer emphasized, but with actual victories in short supply, it helps to recognize moral ones.

“Well, we need to, because if you’re just determined by the letter at the end of the game, we’d all be crushed,” said Clint Hurdle, who led the Rockies to their only pennant in 2007 and returned in April as a coach.

Advertisement

“I mean, this is rare air. We were in an Uber the other day in Chicago and the driver had a White Sox hat on. We were having a conversation and he goes, ‘By the way, will you guys start winning some games? Because it took us 60 years to beat the record last year, so people would actually talk about us for a little bit.’”

The Rockies could still smash the 2024 White Sox’s modern record of 121 losses in a season; they will greet the Mets at Coors Field on Friday with a 12-50 record, which works to a 131-loss pace. But things finally started turning this week in Miami, where the Rockies swept a three-game series from the Marlins. Schaeffer saw it coming.

“We’re going through a gauntlet of a schedule right now,” he said. “It’s just — the difference is in the margins, the in-game execution on a more consistent level to take those one-run games and flip them. Honestly, I don’t think we’re far off from winning games because the past two weeks we’ve been playing good, solid baseball.”

This is the Rockies’ seventh losing season in a row since 2018, the last time they reached the playoffs. The last two years were the worst in franchise history, each with more than 100 losses, but there was reason to expect at least some improvement.

Three veteran starters — Kyle Freeland, German Marquez and Antonio Senzatela, who make $38 million collectively — were all finally healthy. They’ve made all their starts but gone 4-25 with a 6.37 ERA.

Some young position players offered hope; shortstop Ezequiel Tovar and center fielder Brenton Doyle won Gold Gloves last season and first baseman Michael Toglia slugged 25 home runs. All have regressed, with Toglia now in the minors.

“It was kind of the perfect storm,” general manager Bill Schmidt said, mentioning the struggling rotation and several injuries. “I thought we’d play better defense, but at one point we had four shortstops in the IL. I mean, even the guys we brought from the minor leagues went on the IL; I had to go out and get Alan Trejo, who used to play for us, just to have a shortstop.

Advertisement

“It is what it is. We’re trying to get better. I feel bad for our fans. They’re loyal, they care. Our ownership’s good, they care. We’ve got to turn it around somehow.”

Schmidt disputes the idea, widely held around the league, that the Rockies are too insular, too loyal to their employees and prospects to cultivate new voices or accept the reality that they’ve fallen behind other organizations.

But Hurdle, who guided Pittsburgh to three playoff berths in the 2010s and re-joined the Rockies in December 2021 as a special assistant, concedes that it’s a valid point.

“There’s too much information out there, there’s too many other teams doing things well in areas that we could use improvement to not knock on some other doors,” Hurdle said. “And I think we’re doing more of that. We have added to the R&D staff, because three years ago it was pretty much non-existent and now we’ve got (about) 20 people and it’s become more real. We put ourselves probably behind the pack in some areas and it’s made it tough. Now we’re catching up, and it is tough to play catch-up, initially.”

Institutional knowledge can be important, of course, and Schaeffer — technically the interim manager, as Hurdle is an interim hitting and bench coach — managed several of the Rockies in the farm system. Only one manager in the majors, the St. Louis Cardinals’ Oli Marmol, 38, is younger than Schaeffer, who looks as if he could still play.

“He’s just a super hard-working dude who gets the most out of players,” outfielder Sam Hilliard said. “Guys want to play hard for him, guys want to work for him and win for him. And he always makes it clear, like: ‘This is the standard we want to hold you to. I know we’ve lost a lot this year, but we can’t get into that rhythm of, ‘Oh, we lost again, it’s OK.’ It’s never OK.’”

Every team needs outside ideas to grow, Schaeffer said, but he’ll fiercely defend the purple and black. He said he would always be grateful to owner Dick Monfort for paying the minor league staff in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic led to the season’s cancelation. And he’s still a bit astonished that the Rockies hired him in the first place; Schaeffer hit just .214 in their system, then became a Class A hitting instructor.

Advertisement

“He was a grinder,” said Schmidt, the Rockies’ lead scout when the team drafted Schaeffer from Virginia Tech in 2007. “His baseball IQ was real good. There are certain types of guys you identify: they’re baseball people.”

In Colorado, the baseball people are trying to avoid baseball infamy, celebrating subtle improvements in hopes of more winning weeks.

“It’ll be a summer of coaching and teaching,” Hurdle said, “and we’re gonna have to have a lot of patience.”

Big honor for Big Unit

The Seattle Mariners announced this week that they will retire Randy Johnson’s No. 51 in a ceremony during the 2026 season. It’s a long overdue honor for Johnson, whose extraordinary pitching in 1995 helped save baseball in Seattle.

Johnson, whose 4,875 strikeouts are the most ever by a lefty, shares 51 in Mariners lore with Ichiro Suzuki, who asked his permission to wear it when he signed with Seattle after the 2000 season. Johnson, by then, was pitching for the Arizona Diamondbacks, the team he represents in the Hall of Fame.

“He had written a nice letter asking if he could wear the number 51, knowing that I had worn it for 10 years, and I had no problem: ‘Wear it and enjoy it,’” Johnson said on Monday. “And then he went on to have a Hall of Fame career. But there really was never any significance to me wearing the number 51.”

The Mariners will actually retire the number twice: first for Suzuki on Aug. 9, after his ceremony in Cooperstown. That’s how Johnson wanted it.

“I know the significance of Ichiro and his accomplishments, and I didn’t want to interfere with his Hall of Fame induction this year or his number retirement this year,” Johnson said. “And so the one contingent factor that I had was that if this was going to happen, that I didn’t want to take away anything from his deserving day, and it would have to be done a different day, a different year.”

Advertisement

Johnson, who wore 51 with Arizona, switched as a New York Yankee because Bernie Williams already had it; his children suggested 41, to match his age at the time. He also wore 57 briefly with the Montreal Expos and pitched two games for Seattle while not wearing 51.

Mired in a five-start losing streak in July 1992, Johnson reversed his digits and wore 15 for a start at Yankee Stadium. He walked nine that day, lost again, and switched back to 51. The next season, he wore No. 34 for a start at the Kingdome on Sept. 26, when he reached 300 strikeouts in a season for the first time.

Johnson wore 34 that day to honor Nolan Ryan, who had suffered a career-ending elbow injury on the same mound four days earlier and was instrumental in turning around Johnson’s career.

During that frustrating 1992 season, Texas Rangers pitching coach Tom House invited Johnson, a fellow USC alum, to watch Ryan throw in the bullpen before a game. Ryan demonstrated the proper way to land in a pitcher’s delivery — on the ball of your foot, not your heel — and Johnson used the tip to streamline his momentum to the plate and finally harness his overpowering stuff.

After leading the majors in walks in 1990, 1991 and 1992 (each time with at least 120), Johnson never walked 100 again. He went 75-20 over the next five seasons and was on his way to becoming the last pitcher to earn 300 victories — maybe ever.

“I think if someone’s going to do it, it’ll be Justin Verlander,” Johnson said. “And then after that, I don’t think you’ll probably see that happen again.”

Verlander, 42, is winless in 10 starts for the San Francisco Giants this season and is on the injured list with a strained pectoral muscle. He has 262 career victories.

Gimme Five

The Reds’ Wade Miley on his many brushes with fame

Wade Miley returned to the majors this week for the 15th season of a highly eventful career. Miley, who had Tommy John surgery in February 2024, rejoined the Cincinnati Reds when Hunter Greene landed on the injured list with a groin strain.

Advertisement

Miley, 38, was a rookie All-Star for the Diamondbacks in 2012. He’s never made it back to that stage, but along the way — with Boston, Seattle, Baltimore, Milwaukee (twice), Houston, Cincinnati (twice) and the Chicago Cubs — he’s done a whole lot of other stuff.

That includes some things he can’t really do anymore. Miley once homered in a game in San Francisco, long before the NL adopted the designated hitter. In 2018, he started consecutive games for the Brewers in the NLCS — the first as a surprise opener, when he faced just one hitter. That won’t happen again because of MLB’s three-batter minimum rule.

Miley recently offered a memory of five different achievements — well, technically four, and another that wasn’t memorable at all.

Hitting a home run in 2013: “What made that one really, really cool was that none of us had gotten a hit yet. And when I got off the bus, right when I got to the clubhouse, for whatever reason, I was like: ‘I’m hitting a freaking homer today!’ I don’t know if I was calling my shot — I was just talking (smack), I probably did that before every game.”

Giving up Adrián Beltré’s 3,000th hit in 2017: “There was pressure in that moment. I went 3-0 (in the count) and I was getting booed. I was like, I’ve gotta throw him a strike. And then he got me. But it was cool, it’s a very special hit for him and I get goosebumps looking back. He signed some stuff for me, and I’ve always been a huge Beltré fan. So that was cool. Félix Hernández was upset with me, though, because they were coming in the next night and he was due to face him. They’re like best friends and he had told him not to get it off me.”

Starting as an opener in the 2018 NLCS: “I knew the plan. I didn’t necessarily love it, but that’s what we thought would be the best. It was weird, being able to do that for a warm-up and get to a decent intensity, knowing I’m starting the next game as well. There was a fine line of how hard I went at it.”

Throwing a no-hitter for the Reds in 2021: “What stands out about that was the excitement it brought everybody, the way the team embraced me afterwards and how it was so special for them. I’ll never forget turning around, watching Kyle Farmer throw across the diamond, Tucker (Barnhart) just being in my lap. I couldn’t believe how soon they all got to me.”

Advertisement

Pitching an immaculate inning in Arizona on Oct. 1, 2012: “I don’t even remember doing that. Where was that?”

You’re excused, Wade. Nobody else seemed to notice, either. The broadcasters weren’t even narrating the action:

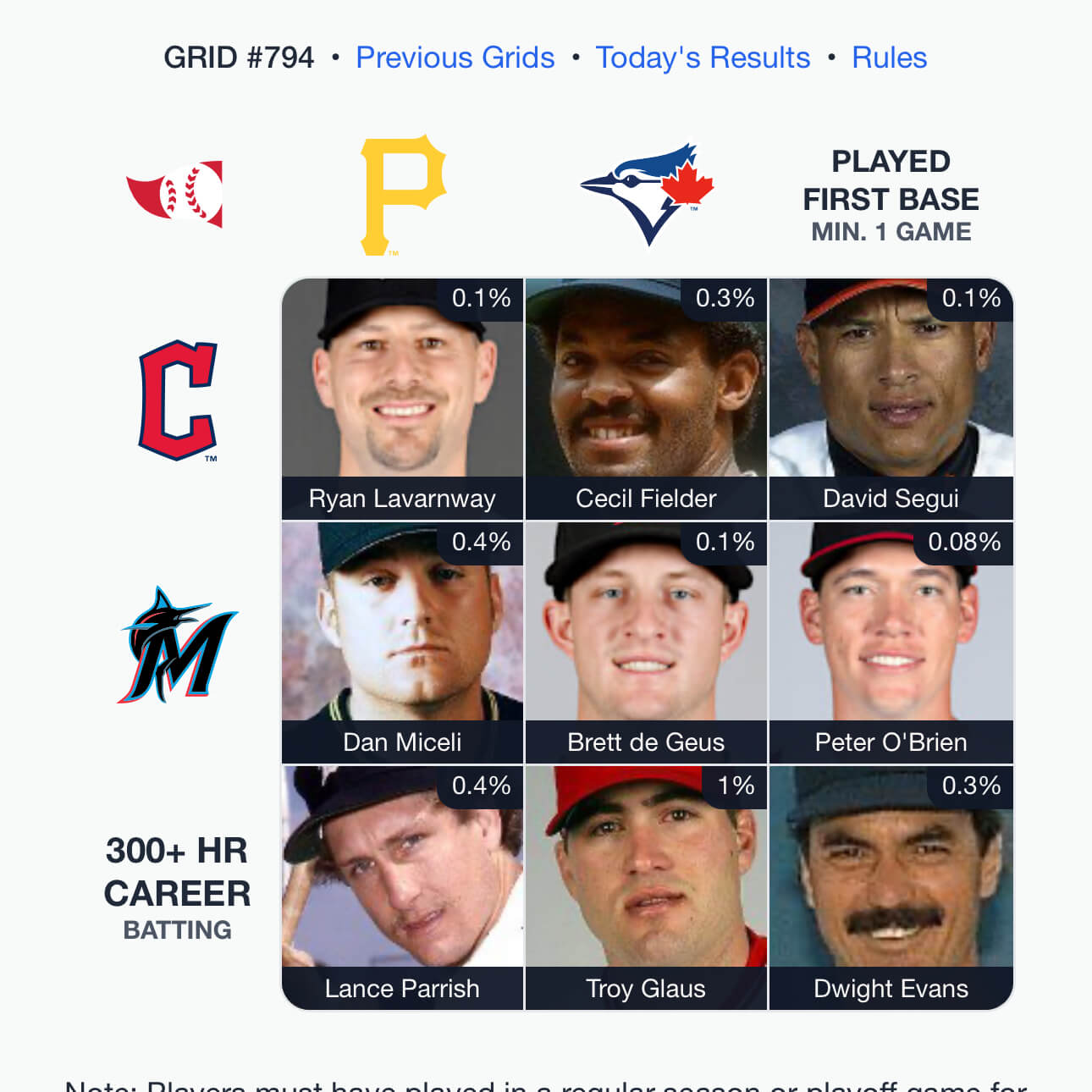

Off the Grid

Peter O’Brien, Marlins first baseman

The Marlins have employed 114 first basemen in their 33-year history, from Jeff Conine (1,014 games) to Jack Winkler, who made his major-league debut last week. Only one earned a measure of infamy simply by catching a foul ball.

That was Peter O’Brien, who played for seven teams as a pro but reached the majors with only Arizona and Miami, hitting .209 from 2015 to 2019. As the Marlins’ first baseman on Sept. 29, 2018, O’Brien had the distinction of ending the career of the Mets’ captain, David Wright.

With his career effectively over because of spinal stenosis, the 35-year-old Wright returned to the Mets for two games at the end of the 2018 season. In the last, he was scheduled for two plate appearances and walked in his first. When he came to bat again, the 43,298 fans rose from their seats at Citi Field.

Wright took a ball, then swung at a high fastball, lofting it toward the first base stands. O’Brien drifted over, unsure of how close he was to the wall. He stuck out his glove and snared it, as the crowd howled.

“Part of me felt bad for O’Brien as I walked back to the dugout, staring at my bat, a goofy grin on my face,” Wright wrote in “The Captain,” his memoir with Anthony DiComo. “Most of me was just stunned. Was that really it?”

It was. But at least O’Brien got a cool souvenir from it. A Marlins clubhouse attendant scrawled a note on a baseball, ripping O’Brien for making the catch — and adding Wright’s signature. When O’Brien found it at his locker and learned it was a prank, he sent the ball to the Mets’ clubhouse for the real Wright to sign.

Wright did, and added an inscription of his own: “No, really. You should have let it drop.”

Classic clip

Don Drysdale for Vitalis, 1968

Don Drysdale worked 3,270 1/3 innings in his 1957-68 prime, the most in MLB in that stretch. It’s also about 1,200 more innings than the major-league leader in the dozen seasons before 2025, Max Scherzer, who threw 2,073 1/3. As you may have noticed, times have changed.

Drysdale, a towering figure who spanned the Dodgers’ Brooklyn and Los Angeles eras, is the subject of a riveting biography published earlier this year: “Up and In: The Life of a Dodgers Legend,” by longtime Orange County Register columnist Mark Whicker. This week marks the 57th anniversary of the sixth and final shutout in Drysdale’s 58-inning scoreless streak.

Advertisement

Another Dodger, Orel Hershiser, broke the record in 1988 with 59 scoreless innings to end the regular season and eight more to start the playoffs. Both pitchers paid dearly with their shoulders: Drysdale was finished in 1969, at age 33, and a shoulder reconstruction saved Hershiser’s career in 1990.

Here’s Drysdale cashing in on his streak with a cheeky ad for Vitalis in 1968, co-starring San Francisco Giants manager Herman Franks. It plays on Drysdale’s reputation for loading up his turbo sinker. Cheating used to be so fun.

“Vitalis has no grease, and spreads easily through your hair,” the announcer intones. “If we all used Vitalis, we could help put an end to the greaseball.”

(Top photo of Warren Schaeffer: Dustin Bradford / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)