An unexpectedly competitive, but expectedly entertaining, NBA Finals have transformed from a best-of-seven to a best-of-three, as the Indiana Pacers and Oklahoma City Thunder alternated wins in the first four games.

Recently, they’ve even alternated winning styles, too. The Thunder led most of Game 3, but the Pacers surged ahead with a big fourth quarter, and Oklahoma City pulled the same comeback trick in Game 4.

Through four games, the two teams are separated by just six points, and they could be headed for the first Finals Game 7 since the clash between the Cleveland Cavaliers and Golden State Warriors in 2016. In advance of a pivotal Game 5 (8:30 p.m. ET, ABC), here are seven plays that have defined the tactics and narratives of the 2025 Finals, explaining how the series reached 2-2 and where it might be headed.

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

Let’s start in Game 3, when the Pacers took one of their favorite tactics to the extreme. Shai Gilgeous-Alexander‘s pick-and-rolls have set the stage for a delightful game-within-a-game in the Finals. The Pacers harried him in Game 1, so Oklahoma City tweaked its screening tactics in Game 2, setting more picks high up the court to open space for the league MVP.

Then, Indiana responded, denying Gilgeous-Alexander the ball. If he doesn’t have possession, it doesn’t matter where the Thunder would prefer to screen for him. Through Game 2 of the Finals, Gilgeous-Alexander had brought up the ball on 61% of the Thunder’s possessions when he was on the court, according to an analysis of GeniusIQ tracking data.

But against Indiana’s intense full-court pressure in Games 3 and 4, that percentage dropped by half, as SGA brought up the ball on just 30% of the Thunder’s possessions in each game. That’s a major change of pace for Oklahoma City’s offense: Out of 342 games that Gilgeous-Alexander has played over the past five seasons, these were his second- and third-lowest percentages.

After Indiana’s first made shot of Game 3, Andrew Nembhard denied Gilgeous-Alexander the inbounds pass, preventing him from initiating Oklahoma City’s offense. And though that first possession still produced a bucket for Williams, SGA never touched the ball.

More often than not, that setup is a win for Indiana — like on this possession midway through the first quarter of Game 3, when Oklahoma City’s most talented offensive player didn’t touch the ball and an out-of-control Williams committed a turnover.

Overall, the Thunder are averaging 122 points per 100 half-court possessions in the Finals when Gilgeous-Alexander brings up the ball, versus just 107 when he’s on the court but doesn’t bring up the ball, per GeniusIQ. That’s not the whole story.

Not bringing up the ball could help Gilgeous-Alexander avoid early fatigue, setting him up for better luck in crunch time, as was the case in Game 4. But it helps illustrate why Indiana’s middling defense has slowed the Thunder, who had the No. 3 offense in the regular season.

Game 4, third quarter: OKC commits a shot clock violation

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

Facing a growing deficit in front of a frenzied Pacers crowd, Oklahoma City called a timeout to regroup. But that plan failed. After Alex Caruso brought up the ball — because of Nembhard’s continued denial of SGA in the backcourt — Isaiah Hartenstein‘s handoff was almost a turnover, then Nembhard stonewalled Gilgeous-Alexander’s attempt to isolate in the midrange.

Eventually, with the shot clock winding down, the ball deflected out of bounds, and after another deflection of the inbound pass, Indiana forced a violation.

This possession illustrates Oklahoma City’s sudden lack of offensive flow. It’s astonishing how much the Thunder have relied on tough one-on-one scoring in this series, as opposed to rhythmic playmaking as a team. The three lowest-assist games of Oklahoma City’s season are:

-

Game 4 of the Finals: 11 assists.

-

Game 1 of the Finals: 13 assists.

-

Game 3 of the Finals: 16 assists. (The Thunder had more than 16 assists in every regular-season game except Game No. 82, when they had 16 with all their starters resting.)

That’s a massive shock to OKC’s system, as the team averaged 27 assists in the regular season and 25 in the playoffs until the Finals. In Game 4, Gilgeous-Alexander didn’t have an assist for the first time in five years.

Game 4, fourth quarter: Aaron Nesmith fouls Gilgeous-Alexander

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

Though Nesmith was the Pacers’ key defender in the Eastern Conference finals, as he had the greatest success guarding the Knicks’ Jalen Brunson, Indiana prefers Nembhard to guard Gilgeous-Alexander. Nembhard has matched up against Gilgeous-Alexander on 187 possessions in the Finals, per GeniusIQ, versus 119 for the rest of the Pacers combined.

The results show why. Out of 27 defenders who have guarded SGA for at least 10 matchups this postseason, his three highest points-per-matchup figures are against non-Nembhard Pacers: Bennedict Mathurin (0.89 points per matchup), Nesmith (0.73) and Myles Turner (0.73). For comparison, Gilgeous-Alexander has scored only 0.33 points per matchup against Nembhard.

Gilgeous-Alexander is still getting his typical share of points in the Finals (32.8 points per game, versus 32.7 in the regular season), but Nembhard is making him work a lot harder for them than anyone else.

Those numbers might reflect a small sample, but down the stretch of Game 4, the Thunder geared their offense toward shifting Nesmith onto Gilgeous-Alexander instead. Oklahoma City — which typically asks its guards to set the most picks in the league — repeatedly sent Gilgeous-Alexander to screen for Williams, who was being guarded by Nesmith, to coax Indiana into a switch.

Gilgeous-Alexander set five picks for Williams in the fourth quarter of Game 4 — tied for the most in any quarter of their careers playing together, per GeniusIQ. The other time was the fourth quarter of Game 4 against the Dallas Mavericks in last year’s playoffs, another must-win game for the Thunder. They clearly trust this action in desperate moments.

Against Indiana, those five plays produced excellent results as the Thunder completed their comeback: a layup, a 3-pointer, two shooting fouls (which led to Nesmith fouling out) and an open midrange jumper that he missed. The Thunder evened the series, and Gilgeous-Alexander scored the most points in the last five minutes of a Finals game (15) since 1971.

Game 1, first quarter: Pascal Siakam makes a layup

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

Indiana’s first made field goal of the Finals showcased one advantage for the Pacers: Siakam is too big and too adept at finishing to switch a guard onto him. Cason Wallace is an excellent perimeter defender, but on this play, he couldn’t offer meaningful resistance as Indiana recognized the mismatch, cleared out one side of the court and let Siakam go to work.

Siakam, who won a title with the 2018-19 Toronto Raptors, leads the Pacers in the Finals with 18.8 points and 7.8 rebounds per game, and he’s contributing 1.8 steals and 1.3 blocks. He’s on pace to become the 12th player this century to average 18/7/1/1 in the Finals, joining an elite list: Shaquille O’Neal, Kobe Bryant, Tim Duncan (twice), Dwyane Wade (twice), Kevin Garnett, LeBron James (three times), Kevin Durant, Kawhi Leonard, Anthony Davis, Giannis Antetokounmpo and Andrew Wiggins.

But it’s Siakam’s ability to overwhelm smaller defenders on the block that has had so much impact on the Finals. It’s not just that it allows Siakam to generate easy buckets, which are rare against this historically great Thunder defense. It’s also that Siakam forced Thunder coach Mark Daigneault to change his game plan. For Game 4, Daigneault reinserted Hartenstein into the starting lineup, replacing Wallace to give the Thunder more size.

The Thunder’s double-big lineup opens holes elsewhere, though, because it reduces Oklahoma City’s speed on the floor — which is necessary when countering Indiana’s high-octane attack. The Pacers are well-rounded enough that they force trade-offs from their opponents, and Siakam, with his ability to run the floor and power through defenders at the rim, is the epitome of that strength.

Game 4, third quarter: Nembhard makes a 3-pointer

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

The Thunder allowed the most corner 3s this season, and the Pacers have taken advantage. On this play, some clever Tyrese Haliburton head and ball fakes created an open look for Nembhard. But NBA teams try to avoid helping off the strong-side corner — because this kickout pass would be easy for any guard, let alone the playoff leader in assists per game.

The Thunder are more aggressive with this sort of help than other teams. Usually, that’s to their benefit and they have the personnel to make it work, but Indiana has twisted the Thunder’s tendencies against them. The Pacers are 25-for-52 on corner 3s (48%) in the Finals, versus 27-for-87 (31%) above the break. Corner shots account for nearly half of their 3-point makes on only about a third of their attempts.

For comparison, Oklahoma City has matched Indiana with 27 above-the-break 3s, but has gone only 11-for-33 from the corners. That disparity has granted Indiana 14 more 3s overall, or 42 extra points from beyond the arc.

Indiana’s hot shooting from the corners likely won’t regress much as the Finals continue. Throughout the postseason, the Pacers are shooting 47% on corner 3s. That’s the best mark for any team (minimum 100 attempts) since the Phoenix Suns shot 48% from the corners in the 2009-10 playoffs.

Game 3, first quarter: Obi Toppin makes a layup

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

So, if the Pacers are generating some mismatches, even against the Thunder’s ferocious defense, and are feasting on corner 3s, then why is Indiana scoring just 109.8 points per 100 possessions in the Finals, after topping 116 in the previous playoff rounds?

This bucket gives a hint. It was the result of a dynamite play from Haliburton, who intercepted a pass, created a 3-on-2 fast break and tossed in a sprinkle of razzle-dazzle as he went behind the back in midair and found Toppin cutting to the hoop.

But this sequence stands out, in part, because of how absent that open-court verve, which defines Indiana’s offense, has been in these Finals.

Over the postseason, the Pacers have scored 127 points per 100 chances in transition, versus just 102 points per 100 chances in the half court, per GeniusIQ. Among teams that advanced at least one round, only the Minnesota Timberwolves had a larger gap, so it’s crucial for Indiana to run.

That’s easier said than done against Oklahoma City. Transition play has accounted for 11% of the Pacers’ chances against Oklahoma City, per GeniusIQ, versus 15% in the first three rounds and 16% in the regular season. Indiana was one of the most frequent transition teams earlier in the playoffs but has fallen to the bottom of that statistic against the Thunder.

Minnesota followed a similar pattern: The Timberwolves had an above-average transition rate in the first two rounds, but a mere 11% transition rate against the Thunder in the conference finals. That’s a big reason the Timberwolves’ offense sputtered and Oklahoma City reached the Finals, and it’s why Indiana is struggling to score more than ever.

Game 2, second quarter: Indiana loses the ball out of bounds

Preview for tomorrow’s piece, before Game 5 pic.twitter.com/CdJ3UchN0N

— Zach Kram (@zachkram) June 16, 2025

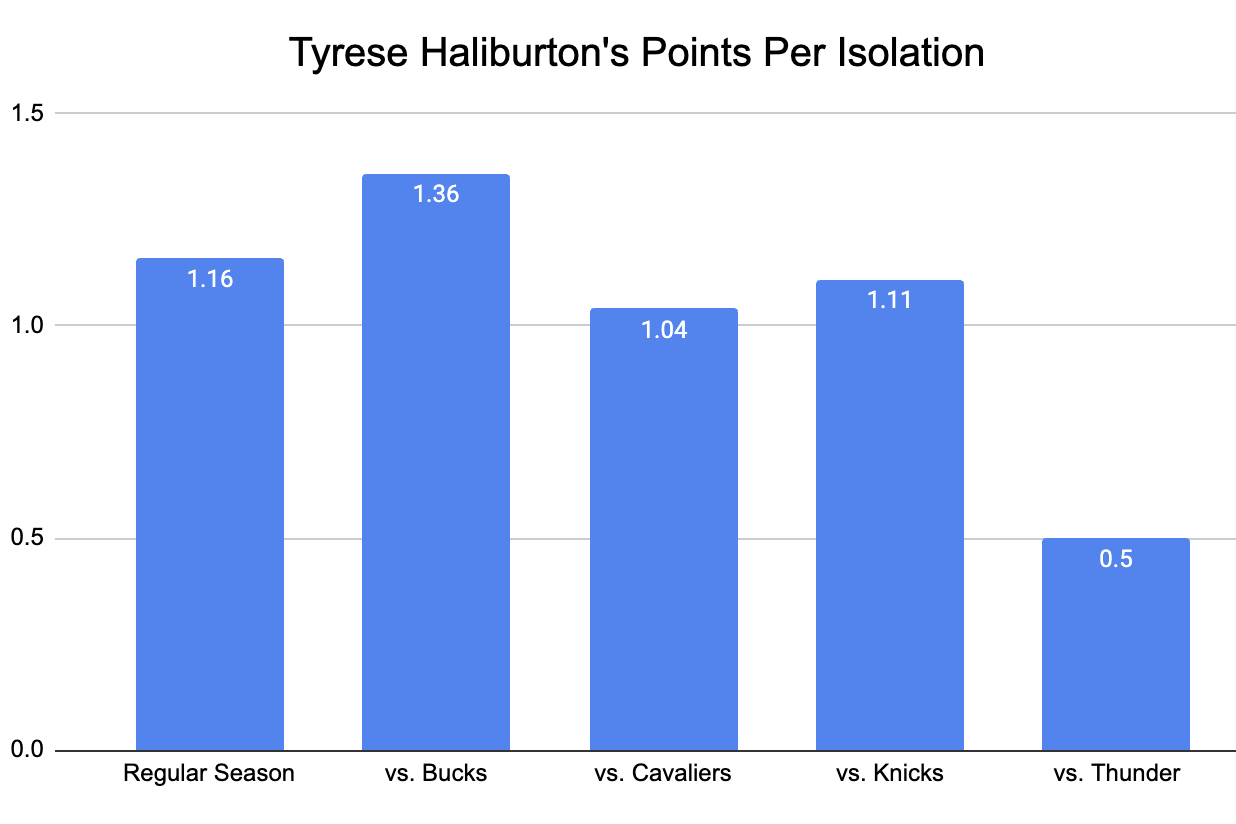

Haliburton doesn’t have the reputation of an isolation master, but his numbers tell a different story. Over the past three seasons, Haliburton leads all high-volume players with 1.16 points per isolation that leads directly to a shot, turnover or foul, per GeniusIQ. (SGA is second, 0.002 points per iso behind Haliburton.)

That effectiveness mostly continued through the conference finals. But against Oklahoma City, the Pacers have scored just 0.50 points per Haliburton isolation. It’s a small sample, but an important one, because several of Haliburton’s failed isolations came as Indiana’s offense stalled down the stretch of Game 4.

On this play from Game 2, Haliburton failed to find an opening against Chet Holmgren in space, ultimately forcing a pass that trickled out of bounds for a turnover. Haliburton has maneuvered past Holmgren for contested layups a couple of times in the series, but this early play presaged his difficulty attacking any Thunder player by himself.

While Oklahoma City and Indiana boast two of the deepest rotations in the league, this closely contested Finals might be decided in crunch time by Haliburton and Gilgeous-Alexander, and whether they can beat their man one-on-one. In Game 1, SGA missed a midrange jumper, and Haliburton took advantage with a game winner.

In Game 4, Gilgeous-Alexander tormented Nesmith down the stretch while Haliburton squandered a couple of crucial isolation opportunities, letting the Thunder back into the series and setting the stage for a furious best-of-three to finish the 2024-25 season.