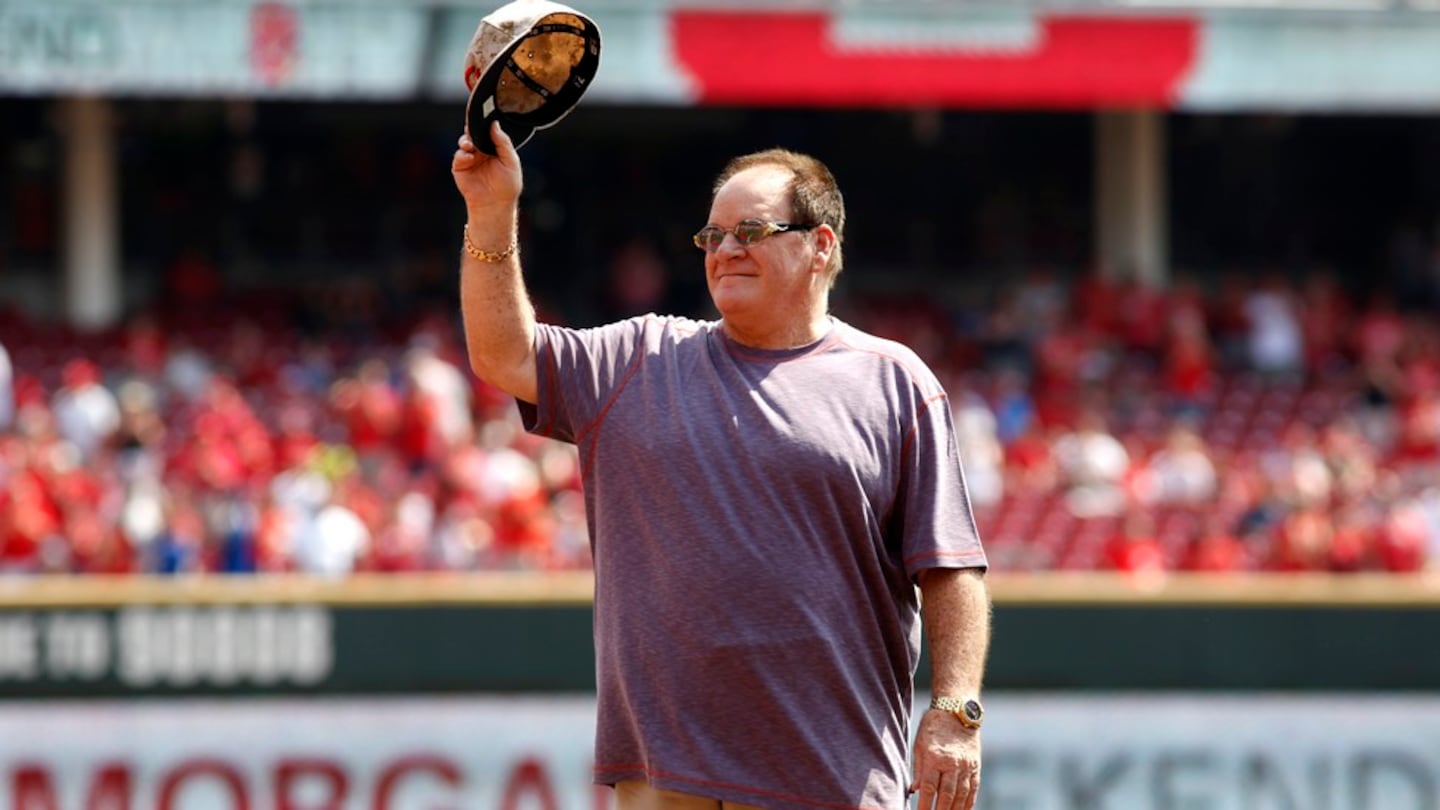

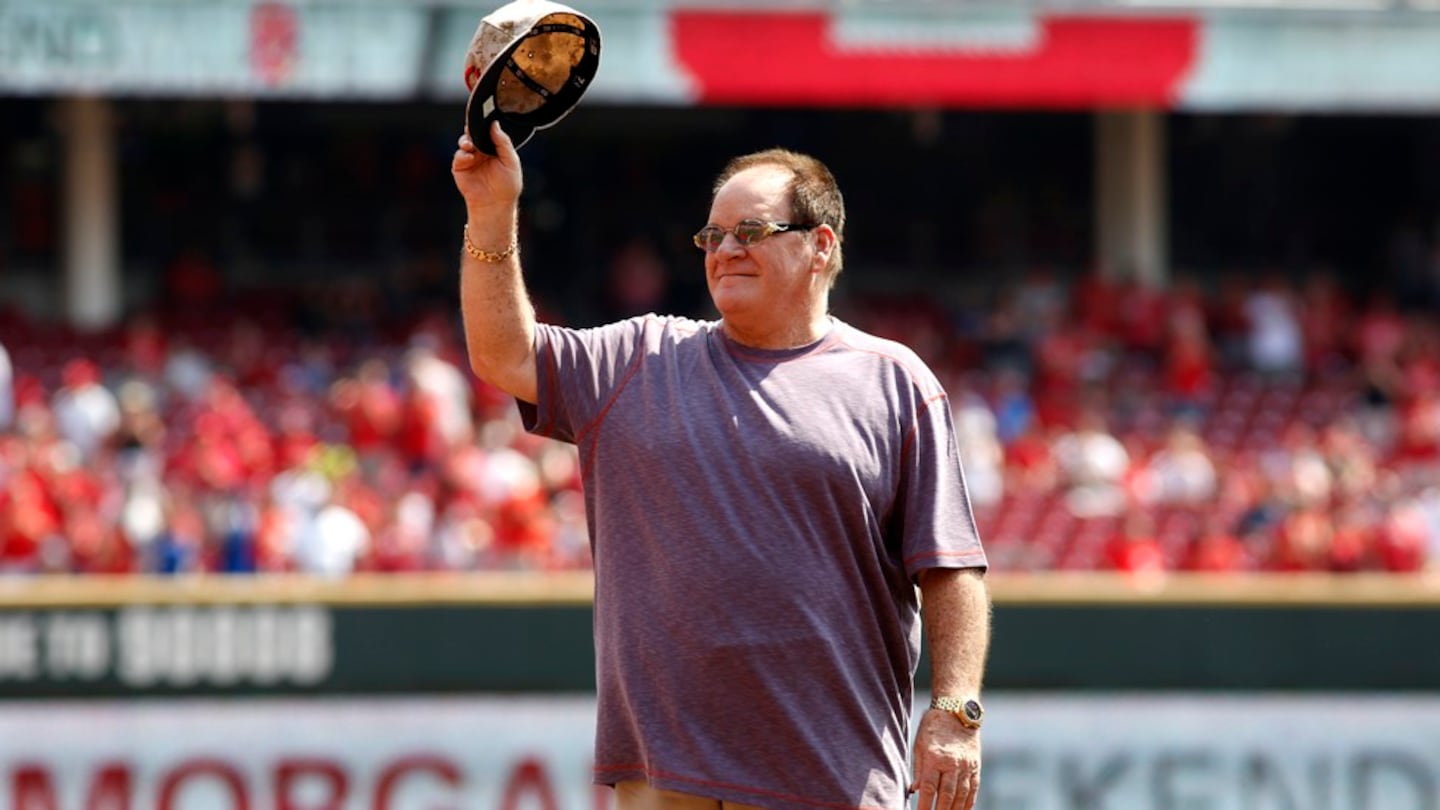

On Tuesday, Rob Manfred, Major League Baseball’s commissioner, released a letter that once would have been unthinkable, at least before he visited the White House last month: He lifted the lifetime ban on Pete Rose that made him ineligible for induction in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

In 1989, Rose, one of the game’s most legendary and scandalous players, accepted a permanent spot on baseball’s ineligible list after then-commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti reviewed documentation that Rose violated the sport’s sacrosanct Rule 21 when he bet on baseball games while he was the manager of the Cincinnati Reds.

A crucial subsection of Major League Rule 21, which hangs in every MLB locker room, states, “Any player, umpire or club or league official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform, shall be declared permanently ineligible.”

Which is exactly what Rose did.

But in a somewhat contradictory letter to Jeffrey M. Lenkov, an attorney representing the Rose family, Manfred wrote that, “once an individual has passed away, the purposes of Rule 21 have been served. Obviously, a person no longer with us cannot represent a threat to the integrity of the game. Moreover, it is hard to conceive of a penalty that has more deterrent effect than one that lasts a lifetime with no reprieve.”

Rose died last year at 83.

Other former players, including “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and seven of his 1919 Chicago White Sox teammates — remembered for the “Black Sox scandal” when they were accused of having consorted with gamblers to throw the World Series — were also posthumously removed from the ineligible list.

In the nearly 40 years since Rose’s voluntary acceptance of a ban, no commissioner has sought to remove him from the permanently ineligible list. For 10 years, Manfred was one of them — then he met with President Trump last month. Though Manfred didn’t reveal the specifics of his conversation with Trump, this much was clear: The countdown had begun on the end of Rose’s ineligibility and Trump scored another bent knee to add to his growing collection of capitulators.

Manfred never mentioned the president in his letter to Lenkov. He didn’t have to.

For years, Trump pushed for Rose’s reinstatement. In February, the president said that he would pardon Rose, who once described himself as a “Donald Trump guy.” No one should be surprised — like Trump, Rose behaved as if unbound by rules that applied only to weak men. He lied about gambling on baseball for more than a decade and only admitted his guilt to juice sales of his 2004 book, “My Prison Without Bars.” He spent five months in jail on federal tax evasion charges.

In 2017, Rose was accused of statutory rape by a woman who said that he had sex with her when she was a minor. When a female reporter asked Rose about the allegation years later, he replied, “It was 55 years ago, babe.” He then berated another reporter for also broaching the topic. “Who cares what happened 50 years ago?” Rose said. “You weren’t even born. So you shouldn’t be talking about it, because you weren’t born. If you don’t know a damn thing about it, don’t talk about it.”

A Donald Trump guy indeed.

Evaluated solely on his career stats, Rose should have been a first ballot Hall of Famer. He remains the game’s all-time leader in hits with 4,256. He also holds records for the most games played (3,562), at-bats (14,053), and plate appearances (15,890). He appeared in 17 All-Star games and won three World Series titles.

But Rose believed that his own selfish pursuits were more important than protecting the integrity of the game. He never showed remorse for the actions that got him booted from the game he claimed to love because he never believed he’d done anything wrong. Rose preferred to see himself as the victim, someone treated unfairly despite the fact that he’d brought all of his troubles down on himself.

Sound familiar?

Now, despite all of it, Rose could receive baseball’s highest honor — from a permanent ban to permanent enshrinement among the greatest to ever play the game. His fate will lie with the Hall’s Historical Overview Committee, which will submit eight names for the Classic Baseball Era Committee to evaluate players who made their biggest impact on the game prior to 1980. A vote would come in December 2027.

While Rose’s death should have ended a shameful chapter in baseball history, he could be inducted into the Hall in 2028. But the man who became a national embarrassment to the national pastime serves as another example of the convicted felon president making himself an arbiter of twisted justice to the benefit of his favorite criminals, insurrectionists, and miscreants.

Renée Graham is a Globe columnist. She can be reached at renee.graham@globe.com.